Niko Niemisalo

The briefing note “Tourism Safety and Security: Findings from Tourism Intensive Finnish Lapland” describes the topic of tourism safety and security and then presents successful best practices that were developed in Finnish Lapland to tackle the challenges of tourism safety and security systems, describing the main actors on the regional, national and international levels.

The published briefing note is a deliverable of the European Dimension on Tourism Safety and Security project (ESF, 2012-2014) and has been co-created with partners in the project as well as the regional, national and international network of Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland.

“The tourism safety and security network model, developed in Finland, is utilised in developing safety and security throughout the whole of the Arctic region”

- Arctic Strategy of Finland 2013 (50), translated from Finnish Introduction

Introduction

For Finnish Lapland, tourism is a strategically important livelihood. Its development as a business requires innovation, faith in one’s own skills, hard work, a creative approach and an understanding of parallel global and regional dynamics. Furthermore, all actors must understand the dynamics of the postmodern service economy with respect to the more traditional industrial economy. Safety and security management in the tourism industry requires novel approaches that are not within the spheres of traditional organisation safety and security management. The actors in the Tourism Safety and Security System in Finnish Lapland have noticed that new developments in safety and security take place within networks and value chains that require new methods and tools.

The purpose of this briefing note is to describe and disseminate the approaches, activities and actors of Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland and, in so doing, raise awareness of this regional innovation, following the guidelines of the Finnish Arctic Strategy (2013) referred to above. The aim of this dissemination is to enhance safety and security operations in sparsely populated areas through the more effective use of existing resources.

Finland has long been a pioneer in providing a broader understanding of safety and security, for example, within the initiatives of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Northern Dimension, the Rovaniemi Process and the Helsinki Process. Furthermore, developing safety in tourism fits well with the general national image of Finland.1 This briefing note is a deliverable of the European Dimension on Tourism Safety and Security project (ESF, 2012-2014). It explicates the best practices of Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland and international network building (ESF 2012-2014). The consortium acknowledges the support of the European Union and is grateful for the input of all partners, who made this project possible – the Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland and the corresponding work within the international Tourism Safety Network.

Theory: Safety and Security as Concepts

As concepts, safety and security have many meanings. In everyday speech they have several connotations. They refer to the subjective experiences of individuals as well as social relations. Safety and security can be understood as the absence of a threatening factor (van Steen 1996) or, for example, the presence of a negligent state of mind (e.g. Laitinen 1999). According to state-centric and traditional safety and security understanding, the sovereignty and sanctity of a state are crucial. This realist and neo-realist approach understands safety and security as “given” from state structures in which the important actors in modern society include military organisations, the police and, for example, border guards (for safety and security as “given” see Waltz 1979 and for a critique see Wendt 1999.)

Gradually safety and security have changed from a state-owned and state-defined virtue to a societal value and aim. The growth of interdependency, globalisation, environmental and climate change, cross-border interaction and the network society have challenged the traditional state-centric approach. New approaches to safety and security require the extension of our understanding of safety and security. This refers to the discussion on the transnational, idealistic and constructivist approaches that focus on social and civilian safety and security. The approach widens the agenda of the discussion by bringing the environment and economics into the discussion on safety and security (see e.g. Buzan et al. 1998). Environmental questions have appeared as security issues in questions related to environmental disasters and sustainability (see e.g. Dalby 2002). The economic approach highlights themes such as managing an economic crisis and the just allocation of financial resources within society and global systems (Hall et al. 2009).

According to its broader understanding, safety and security is based on human beings and is constructed “bottom-up” (see Kerr 2010) by being based on grass-roots level basic needs. The social security system, health care and other welfare services and associations represent this agenda as producers of safety and security. According to Campbell (1998), we live in societies where safety and security are the utmost virtues. However, these virtues are always, at least, partly out of reach. No individual or state can reach absolute safety and security. This poses a challenge to all in the safety and security research and development community due to the high demands for safety and security in modern society – with its multiple risks and uncertainty. In the sparsely populated Arctic region this issue is even more challenging, though positive developments are taking place (see e.g. Heininen 2005).

As a concept, tourism safety and security is broad and it combines state-centric, traditional security with more individual-focused, softer safety theories. In the tourism safety definition, process-thinking takes into account the safety and security needs of the customer, company and operative environment. According to the broader thinking on the issue, safety and security is formulated bottom-up – from people and local community needs and the grass-roots level. Social groups, such as ethnic minorities, define their safety and security needs between the individual and state and also across state borders. Similar to this broader thinking on safety and security, social security, health care systems and other well-being services and associations also represent safety and security policies

| Actor that defines safety and security | Main safety and security questions | Producers of safety and security |

|---|---|---|

|

Security of state, national security | Military organisation, police force |

|

Communal security-safety, environmental safety and security | Associations, 3rd sector |

|

Personal safety and security, work related (safety) | Local community, municipality |

Figure 1 : Typology of safety and security frameworks (source: Iivari & Niemisalo 2013).

Together with the several scholars that we have cooperated with on this theme, we have noticed that research on tourism safety and security requires broader safety and security thinking. Furthermore, it is multidisciplinary work. Several initiatives to proceed with the topic have been made already (see e.g. Botterill & Jones 2010; Mansfield & Pizam 2006). The initiative developed in Finnish Lapland, i.e. Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland, builds a holistic approach based on the previous work and research that has been already implemented. Our home organisation, the Multidimensional Tourism Institute, provides an excellent environment for this development as it combines academic education and research (University of Lapland), applied science (Lapland University of Applied Sciences) and vocational education (Lapland Tourism College) on tourism studies into a unique combination of research, education and innovation (see: http://matkailu.luc.fi/Hankkeet/Turvallisuus/en/Home).

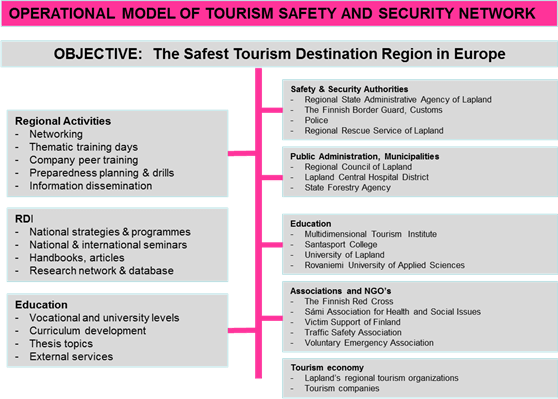

Practice: Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland as an Operative Model

Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland is an innovative approach developed by various actors in a regional, national and international partnership, combining theory and practice. It has been co-financed by the European Union (ERDF, ESF) and it binds together the theoretical approach on the wider understanding of safety and security with practical level activities in sparsely populated Finnish Lapland. The activities are not coincidental as, on a national level, hospitality and voluntary activities designed for international tourists have a long tradition in Finland, for example, the Voluntary Road Service at the Helsinki Olympic Games in 1952.

Therefore, Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland is not without predecessors or parallel activities. On the contrary, innovation in the activities can be seen as resulting from strongcooperation with previous and existing parallel activities as well as the understanding of the contexts in which they are implemented. Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland was implemented in practice as a network that has regional, national and international level members. It provides safety and security education for tourism destinations, tools for crisis communication, safety and risk management and foresight as well as quality. The approach has been identified as a national (Diamond Act 2010) and European (EPSA 2013) best practice. The network includes private companies, public authorities and associations. The activities are especially planned for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). It is an operative model that is possible to tailor to other operative environments based on our customers’ needs. This idea has gained support from regional level strategies, from the Finnish Arctic Strategy (2013) and also from the EU (for more information, see: www.luc.fi/matkailu/turvallisuus/en).

As an operative model the tourism safety and security development activities have existed since 2009. The activities have taken place in 14 tourism destinations within sparsely populated Finnish Lapland and have included hundreds of educational events, drills and company sparrings for tourism companies and SMEs, non-tourism companies, public authorities, associations and other actors. The participating tourism destinations are Enontekiö, Utsjoki, Levi, Ylläs, Saariselkä, Pyhä-Luosto, Kemijärvi, Posio, Rovaniemi, Meri-Lappi (Kemi and Tornio regions), Salla, Muonio, Pello, Ylitornio. Other actors in the Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland are presented on our web-site.2

The education and training events have taken place in tourism destinations in Finnish Lapland. The key idea behind the training has been to enhance the safety skills of the enterprises, public authorities and local populations of the municipalities that operate in and around tourism destination environments. The key problems they tackle are long distances and a lack of safety and security resources combined with a significant increase of the international population during tourism seasons. This results in risks that would cause immediate economic losses and indirectly do major harm to the regional and national image if they occurred. Our core idea has been to create sustainability by committing the local population, public authorities, associations and other actors to safety and security skills and education. The cornerstones of our activities are:

• Listening closely to customer needs (safety and security end-users, tourism enterprises, associations and other third sector organisations, citizens in municipalities close to tourism destinations)

• Active network building: regional, national, international

• Creating practical tools for companies and SMEs

• International cooperation and maintaining our expertise by continually implementing multidisciplinary research into the topic

(Source: Qualitative interviews of the tourism safety experts in Finnish Lapland, April-June2014)

The approach has gained recognition due to its innovative and cost-efficient approach. The National Diamond Act award it received is the highest national recognition for safety and security innovations. This recognition has supported our international network building, indicated by European EPSA2013 award given to the network in November 2013. The significance of these awards is they were awarded after independent peer review and recognition. The internationalisation process serves all actors in the network, especially the tourism industry and SMEs. This briefing note is a co-creation of a particular internationalisation project (European Dimension on Tourism Safety and Security, ESF 2012-2014). The project lead partner is the Multidimensional Tourism Institute, which is a key initiator in the network building and has chosen tourism safety and security as its spearhead theme in RDI. This strategic choice is supported by Lapland University of Applied Sciences, which has chosen safety and security as a strategic priority.3 Other partners are Lapland State Administrative Agency and Lapland Hospital District, who both play crucial roles in tourism intensive Finnish Lapland.

Conclusion

The purpose of this briefing note has been to disseminate the theoretical and practical approaches that have created the presented best practice for developing tourism safety and security: the Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland. The briefing note is also a material package enabling the dissemination of information about our best practices in this field. This is one way for us to be able to respond to the request made by the Arctic Strategy of Finland (2013), encouraging us to spread information about our regional innovation (best practice) to all Arctic countries. Safety and security are at the core of all responsible business, and a tourism destination that is not interested in safety and security will lose its competitive advantage sooner or later.

The briefing note introduced the topic and then presented the theoretical starting points on the concepts of safety and security research, demonstrating it to be a wide and multidisciplinary research field. Next, the practical operative model, main activities and internationalisation of the Tourism Safety and Security System in Lapland approach were presented. The activities are based on combining theory and practice. This combination is challenging but crucial for successful research and development activities. We believe that when researchers enter into dialogue with practitioners, they gain essential data for generalising the actual problems faced, making it possible to support the process of presenting these problems to a wider audiences as well as decision-makers, thus helping to solve these problems. When tourism practitioners can talk with research actors, it makes it possible for them to develop a broader understanding of the causes behind the problems, empowering them to find solutions from the correct sources. We welcome all countries in the Arctic in joining our common endeavour – contact us!

Notes

- In the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs there is a separate formal committee on safe travelling, see: http://formin.finland.fi/public/default.aspx?contentid=50470 (in Finnish only). See also: http://matkustusturvallisuus.fi/. The Tourism Safety and Security in Lapland initiative presented in this briefing note is a unique regional innovation (best practice) for all tourism actors, especially for SMEs. We have strong cooperation with the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs in developing our activities and networking internationally.

- Tourism Safety and Security: http://matkailu.luc.fi/Hankkeet/Turvallisuus/en/Tourism-Safety-and-Security.

- Lapland UAS Strategy: http://www.lapinamk.fi/en/Who-we-are/Lapland-UAS-Strategy.

References

Arctic Strategy of Finland (2013, in Finnish only). Government of Finland. Retrieved from http://valtioneuvosto.fi/tiedostot/julkinen/arktinen_strategia/Suomen_arktinen_strategia_fi.pdf. Accessed 19.6.2014.

Botterill, D. & Jones, T. (2010). Tourism and Crime: Key Themes. Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers.

Buzan, B., O. Waever, J. de Wilde. (1998). Security: A New Framework for Analysis. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Campbell, D. (1998). Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Dalby, S. (2002). Environmental Security. (Borderlines Series #20). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

EPSA 2013, press release on winners in annual EPSA2013 public innovation Competition. Retrieved from http://www.epsa2013.eu/files/Press%20Release_Winners%20November%202013.pdf. Accessed 23.6.2014.

Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Committee on Safe Travelling (in Finnish only). Retrieved from: http://formin.finland.fi/public/default.aspx?contentid=50470. Accessed 23.6.2014.

Hall, M. C., Dallen, T. J. & D.T. Duval (2009). Security and Tourism: Towards a New Understanding? In Hall, M. C., Dallen T.J. & Timothy, D. Duval, T. (eds.) Safety and Security in Tourism: relationships, Management and Marketing (pp. 1–18). New York: Haworth Hospitality Press.

Heininen, L. (2005). Impacts of Globalization, and the Circumpolar North in World Politics. Polar Geography. 29(2, April-June): 91–102.

Iivari, P. & Niemisalo, N. (2013, in Finnish only, Safety and Security Planning in Tourism Company): Matkailuyrityksen turvallisuussuunnittelu. In Veijola, Soile (ed.). Reader in Tourism Research (Matkailututkimuksen lukukirja) (pp. 129-143). Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopistokustannus.

Kerr, P. (2010). Human Security. In A. Collins. (ed.). Contemporary Security Studies (2nd ed.) (pp. 121–135). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Laitinen, K. (1999, in Finnish only). Turvallisuuden todellisuus ja problematiikka: tulkintoja uusista turvallisuuksista kylmän sodan jälkeen (Reality and Problematics of Security: Interpretations of New Securities After the Cold War). Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Mansfeld Y. & Pizam, J. (2006). Towards a theory of tourism security. In Y. Mansfeld & A. Pizam. (ed.) Tourism Security and Safety – From Theory to Practice (pp. 1–28). Oxford: Elsevier Butteworth-Heinemann.

Voluntary Road Service. History of Voluntary road service. Retrieved from http://www.autoliitto.fi/in_english/road_service/voluntary-road-service/. Accessed 23.6.2014.

Waltz, K. N. (1979). Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Wendt, A. (1999). Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Download as PDF