From Regional Transition to Global Change: Dualism in the Arctic

Lassi Heininen, Heather Exner-Pirot and Joël Plouffe

Regionalization, globalization and nationalism cannot be assessed in isolation, independently from one another, nor from a perspective of either convergence or divergence among them. Rather, globalization, regionalization, and nationalism should be captured and studied as forces relative to and overlapping one another, sometimes antagonistic and sometimes cooperative toward each other, but never harmonious. - Arie Kacowicz

The Arctic region seems to be in constant transformation, (geo)politically, economically, culturally and indeed geologically and environmentally. But as we continue to witness significant changes across the Arctic, it is important to remember those political processes and forces in which the events, issues and debates of the region have been evolving over the last decades. The Arctic Yearbook 2013 seeks to identify and assess both historical contexts and contemporary issues/events in a way to better understand and discuss Arctic geopolitics and security.

Arctic Change(s)

In the last century, the Arctic region – or the circumpolar North – was characterised as either a colonial-like marginalized periphery to major powers and imperial centres located more in South and/or a mosaic of homelands to indigenous peoples with their unique identities (Heininen, 2010). For political realists (i.e. strategic planners, military persons, policy-makers or academics working in the disciplines of Political Sciences) the Arctic region is often understood through the lens of strategic studies, the military-political and economic interests of a nation-state, or even super-powers. This perspective does not always take into account earlier legacies, such as colonialism and a capitalist world-economy which tied the Arctic region into the resource needs of European imperial powers (Wallerstein, 1987).

Correspondingly, in classical forms of geopolitics, the entire North has mostly been understood as a vast reserve of natural resources, and military space and testing ground for the performance of sovereignty, national security and economic interests of the Arctic states. During the Cold War period, this world-view frequently went hand-in-hand with intense militarization meaning investments into infrastructure, and constant patrolling, military training and testing, such as nuclear tests, and physical displacement of indigenous communities under the control. This militarized, environmentally damaged and divided Arctic, however, started to thaw in the late 1980s due to increased interrelations between peoples and civil societies of the region, as well as the consequent international cooperation and region-building by the Arctic states.

Followed from this the Arctic and the entire North emerged as a 'new' area for international cooperation – it was said even to be a distinctive region – with co-operative and region-building measures, such as the establishment of the Arctic Council by the Ottawa Declaration in 1996 (AHDR, 2004: 17-21). This implied a recognition that there are several states and non-state actors as well as their willingness to promote deeper international cooperation, particularly environmental protection, in the entire North; and consequently, a significant shift away from the Cold War mentality to define the Arctic as a thinly-populated periphery and military training and testing ground.

In addition to increasing international cooperation, this meant an implementation of extraction-led models concerning energy resources and other potential minerals, and a continuity of a military presence across the region. Furthermore, it meant more sophisticated ways for Arctic states to proactively control their national territories, particularly for the coastal states challenged by growing environmental concerns (due to climate change) in their maritime zones (Canada, Denmark/Greenland, Norway, the Russian Federation and the United States). These trends also revealed how the Arctic is transforming for a platform to host (sub)national, regional/circumpolar and international processes including science and higher education, trade and other economic cooperation, and claims to indigenous autonomy.

By the early-21st century, as a result of the first significant geopolitical change, the three main themes of 'post-Cold War circumpolar geopolitics' were increasing practices of cooperation by regional non-state actors as some sort of 'mobilization' of non-state actors; 'regionalization' of decision-making processes, and region-building by the Arctic states; and a new kind of relationship between the region and the outside world (AHDR, 2004: 207-225; also Östreng, 2008). As a result of these developments, or trends, the entire North became a peaceful area with high stability and without armed conflicts, even if environmental degradation, militarization and intense industrialization, as Cold War legacies, remained as regional challenges.

Further, as it has been discussed (e.g. Heininen, forth-coming), two well-defined discourses on Arctic geopolitics have emerged and shaped the ensuing discussion on the region in the 2010s. First, the geopolitical discourse, on the one hand, reflects the degree of stability and peacefulness enjoyed in the region as a result of the institutionalized international Arctic cooperation (in the post-Cold War era) and, on the other hand, describes the region as a space legally and politically divided between eight Arctic states by mutually recognized national borders with only a few outstanding (and managed) territorial disputes. This state of affairs has been challenged by another, and more explicitly realist, geopolitical discourse arguing that there is a 'race' for natural resources as well as emerging regional conflicts driven by the importance of state sovereignty. According to the latter discourse, state sovereignty is seen to be threatened by climate change, as well as increased interest from outside the region, by non-Arctic states from Asian and Europe, also the European Union, and their security and economic interests.

Northern (In)Security

Indeed, several kinds of relevant regional and global issues and problems do exist in the Arctic and influence geopolitics and Northern security issues. Some of the most relevant issues are the long-range air and water pollutants (such as toxins, heavy metals, radioactivity); climate change with its physical and socio-economic impacts; and problems referring to the mass-scale utilization of energy resources (i.e. extractive industries), and their transportation through new sea routes. All these concerns exercise cumulative impacts on societies, environment and economy, regionally and locally, causing significant and complex changes in the region. Energy security, for example, has appeared in newly contemporary forms and become increasingly important, strategically, within the Arctic states, such as Norway, Russia and Greenland, as a part of exercising and controlling their sovereignty. Correspondingly and at another scale, it has become a part of the larger issue of global security, for instance for China and the European Union, attracted, first, by potentially rich Arctic off-shore hydrocarbon deposits (particularly oil) and, second, an increased access to energy resources due to climate change and thawing sea-ice. Finally, reinforcing the last point, it is the potential of northern sea routes and shipping, particularly new trans-arctic routes, and geo-economics. Although, this growing international interest does not necessarily mean emerging (armed) conflicts in the Arctic, it is also seen and interpreted as a potential threat (perceptions) and risk (calculations) causing uncertainties, where emerging conflicts regarding the environment and natural resources are now part of the security/insecurity equation.

Furthermore, there are two other perspectives that deserve our attention. They both deal with globalization and enable us to approach Arctic geopolitics and Northern security that go beyond the traditional terms of power, conflict and cooperation. The first one is fixated with new and significant changes, which might be called the Arctic 'boom' or 'paradox' perspective (Palosaari, 2012) with indicators, such as rapid climate change, an increase of the utilization of natural resources, new options for energy security and new sea routes. These significant changes have also greatly impacted the traditional Arctic security architecture by expanding the security perspective from traditional and narrow military-oriented to comprehensive, more human-oriented one. The second perspective is focused on the growing global attention toward the Arctic region, and that correspondingly, the region plays more important role in world politics. Issues that are important to this geo-strategic dimensions of today's Arctic include both material indicators, such as sophisticated weapons systems and used advanced technology for utilization of natural resources; and immaterial indicators, such as knowledge, innovation, new methods, and innovative political and legal arrangements (e.g. AHDR, 2004; Heininen, 2010). One more indicator is that, as a response to the recent change(s) and growing international interest, the Arctic states have recently approved their national strategies and policies on the Arctic region, as it was discussed in the Arctic Yearbook 2012, (and the second round of these national strategies has already started), interestingly, there is still a lack of a global perspective in most of those documents.

Thus, it is no wonder why now, ten years later, from the above-mentioned three main themes of the post-Cold War circumpolar geopolitics that a last one – a new kind of relationship between the Arctic region and the rest of the globe – has been implemented and enhanced. While the other two still have clear influence in the region, they have been transformed: circumpolar cooperation by local and regional non-state actors, and sub-national governments, is increasing, and particularly indigenous peoples with their organizations have become subjects of, and create a new kind of 'globalized' regionalism which is challenging state sovereignty while pressuring states to act. Correspondingly, the region-building by Arctic states of the 1990s has meant high stability and institutionalized intergovernmental cooperation, but has also partly transformed itself into national(istic) policies by all littoral Arctic states (not just Russia and Canada, which are often identified as having such policies). Thus, while these two trends are still evolving, the 'state of Arctic geopolitics' today is dominated by interrelationships between 'state of Arctic geopolitics' today is dominated by interrelationships between the (Arctic) region and the rest of the world, and, moreover, the fact that that relationship is also changing.

At the outset, it is in our view possible to argue and conclude that in the Arctic of the 2010s, there are two perspectives – or influential forces – that are impacting the region and its development and resource politics, as well as Arctic geopolitics and northern security, at the same time: first, regionalism/regionalization and region-building; and second, globalization and flows of globalization. Furthermore, they also impact and shape circumpolar (international) relations. Following from this, it is necessary to take both of these forces, as well as their interrelationship, into consideration and discuss their respective impacts – both alone and the related dualism - on further developments across the Arctic to understand, and actively shape, regional and international relations. Furthermore, this sort of dualism, keenly connected with the current culture of an open dialogue and a strong role for research and education, might be a fruitful way to avoid potential conflicts, and concentrate on real issues (of the Arctic), such as climate change and development. Consequently, the theme of the 2013 Arctic Yearbook is "The Arctic of Regions vs. the Globalized Arctic" including several substantial scientific articles and more policy-oriented commentaries with new and interesting approaches on both of these perspectives.

The Arctic of Regions

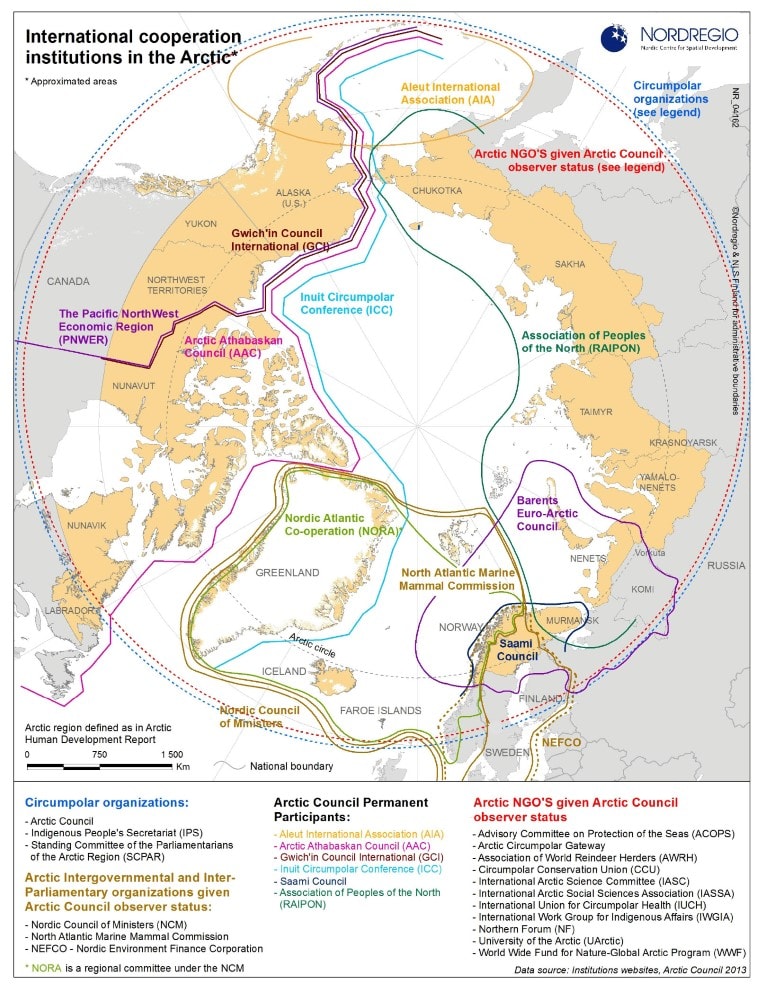

The Arctic emerged, and continues to be defined, by its collection of sub-regions, and the consequent regionalism (Exner-Pirot, 2013). A series of 20th anniversaries, from the Barents Euro Arctic Region (BEAR) to the Swedish Sami Parliament, occurred in 2013, commemorating a period that saw organizational development among indigenous groups, scientific associations and along various northern European maritime and land borders.

The novelty in that era was to construct cooperation within and across the Arctic region, whereas the current era of regionalization has been overshadowed by efforts to promote Arctic cooperation outside the region, whether with states, corporations, NGOs/INGOs or International Organizations. But it would be a mistake to consider sub-regional influence and growth to be over. In the North American Arctic, for the first time, formal Arctic cooperation has developed under the guise of the Arctic Caucus (Alaska, Yukon and Northwest Territories) of the Pacific Northwest Economic Region (PNWER) of western American states and Canadian provinces. Nordic, West Nordic, Barents, and Baltic cooperation is stronger than ever. And if the Arctic Council, and the Arctic region, begins to adjust its balance in favour of environmental protection towards sustainable development, then it will be sub-regional organizations and sub-state units that will need to lead those efforts, in terms of job creation, infrastructure development, accessibility of relevant education and improvement of health services. Canada's Arctic Council chairmanship agenda (2013-2015) provides an indication, but not a promise, of where a focus on these issues may lead the future work of Council members.

The Globalized Arctic

But while regionalism dominated the past, and will need to play a much larger role in the future, 2013 was the year of the globalized Arctic, although globalization is not totally new in the Arctic (see Heininen & Southcott, 2010). It was the year that the relationship between Asia and the Arctic got serious; 'exhibit A' was the accession of a number of Asian states (China, India, Japan, Singapore, South Korea) as Observers to the Arctic Council (Kiruna Declaration, 2013). The free trade agreement between China and Iceland, as an adjunct to the AC observership, made even more acute the impacts of globalization on the Arctic. Asian intentions are not ignoble, but they are global: transnational shipping, resource development, and climate change science. Then of course was the resource development – or in some situations, a lack thereof. The scope and size of Arctic projects makes them inherently global in nature, as only the largest of corporations can pull them off. It also makes them vulnerable to global price trends and market developments. Correspondingly, their potential impacts on the environment have ignited unprecedented "anti-development" movements, most visible through the actions of Greenpeace.

The combination of market and economic pressures can be paralyzing. Note the decline of the Shtockman project in the Barents; Shell's 'pause' from the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas after the Kulluk platform incident in January; and France's Total's unexpected warnings about oil drilling in Arctic waters. Meanwhile a growing interest in rare earths feeds speculation in and impacts politics in Greenland. The commodities market is a global one, and the Arctic economy is based on commodities. Despite the very local implications of resource development, it will get harder to divorce the Arctic from the global economy going forward.

Finally, there is the growing influence of Arctic indigenous peoples far beyond their traditional lands. In 1996, indigenous groups were given a seat at the table of the Arctic Council as Permanent Peoples. In 2013, they are sitting at the head of the table, in the person of Inuk Leona Aglukkaq, Nunavut's representative to Parliament and Canada's Minister to the Arctic Council (and Minister of the Environment). The reaction – sharp would be an understatement – of the international community to Russia's temporary closure of RAIPON; the unprecedented effect the ICC's condemnation of the EU's ban on sealskin products had on its application for observer status at the AC; Greenland's acquisition of its own AC 'seat' for issues of direct relevance, however ill-defined, after a temporary Arctic Council boycott; and China's courting of Greenland are further examples of their evolving position on the world stage – and one that makes no promises of being smooth, as Greenland's elections of this year make clear.

Conclusion

The articles that follow in this edition of the Arctic Yearbook touch on these themes as they document how Arctic geopolitics have rapidly evolved throughout the year. They are testimony of a new era in the Arctic. Produced by authors coming from various backgrounds and different regions of the world – Arctic and non-Arctic states alike – they are in essence a reflection of how the circumpolar North has gained unprecedented attention beyond its borders by individuals who wish to take part in the process of a global Arctic dialogue. They are also articles that offer descriptions and analysis on key issues relevant globally and locally, identifying multiple traditional and non-traditional actors, factors and processes of Arctic change, taking into consideration the contextual and historical evolutions that engage a critical reflexion and debate on geopolitics and security.

Furthermore, the Arctic Yearbook, through its scholarly articles and insightful commentaries, has innovatively brought together scholars and stakeholders to share through this open access platform their respective viewpoints on how Arctic futures are shaping. This collaborative dialogue between science and policy (makers/shapers) – which is tested and further developed in new kinds of academic platforms for interdisciplinary discussion, such as the Northern Research Forum's Open Assemblies - will continue to drive the work of the Arctic Yearbook in the years to come.

To conclude, we would like to acknowledge the academic authors for their thought-provoking articles; our commentators for providing insight into the Arctic from their unique vantage points; President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson for contributing the preface; our reviewers for their constructive feedback on the academic articles; the Editorial Board members for their ongoing guidance; NORDREGIO for map development; TD Bank and Dorset Fine Arts for the cover image; and, Arctic Portal for their invaluable graphic design and web hosting. Finally, thanks to the readers of the Arctic Yearbook 2012 – our inaugural edition – for their interest, valuable feedback and comments.

References

AHDR (2004). Arctic Human Development Report, Akureyri: Stefansson Arctic Institute.

Exner-Pirot, H. (2013). What is the Arctic a Case of? The Arctic as a Regional Environmental Security Complex and the Implications for Policy. The Polar Journal, 3(1), 120-135.

Heininen, Lassi and Chris Southcott (eds.)(2010). Globalization and the Circumpolar North. Anchorage: University of Alaska Press.

Heininen, Lassi (2010). 'Post-Cold War Arctic Geopolitics: Where are the Peoples and the Environment?', in M. Bravo and N. Triscott (eds), Arctic Geopolitics and Autonomy, Arctic Perspective Cahier No. 2. 89–103.

Heininen, Lassi (forthcoming). "Northern Geopolitics: Actors, Interests and Processes in the Circumpolar Arctic." In: Polar Geopolitics: Knowledges, Resources and Legal Regimes. Edited by Richard C. Powell and Klaus Dodds. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, Massaschusetts.

Kacowicz, Arie (1998). Regionalization, Globalization, and Nationalism: Convergent, Divergent, or Overlapping? Kellogg Institute Working Paper #262. Retrieved September 18, 2013 from [http://kellogg.nd.edu/publications/workingpapers/WPS/262.pdf].

Kiruna Declaration (2013). Arctic Council Secretariat: Kiruna Declaration. Kiruna, Sweden, 15 May 2013.

Palosaari, Teemu (2012). 'The Amazing Race. On Resources, Conflict, and Cooperation in the Arctic', in Nordia Geographical Publications Yearbook 2011. Theme issue on 'Sustainable Development in the Arctic though peace and stability', Oulu: Geographical Society of Northern Finland, 13-30.

Wallerstein, Immanuel (1987). 'Development: Lodestar or Illusion?', A Talk at Distinguished Speaker series, Center for Advanced Study of International Development, Michigan State University, October 22, 7–8.

Östreng, Willy, (2008). 'Extended Security and Climate Change in the Regional and Global Context: A Historical Account', in Gudrun Rosa Thorsteinsdottir and Embla Eir Oddsdottir (eds), Politics of the Eurasian Arctic. National Interests and International Challenges, Akureyri: Northern Research Forum and Ocean Future, 16-30.

Lassi Heininen is Professor of Arctic Politics at the University of Lapland, Finland; Heather Exner-Pirot is Strategist for Outreach and Indigenous Engagement, University of Saskatchewan, Canada; and Joël Plouffe is PhD candidate at the École nationale d'administration publique, Canada.