87

Arctic Yearbook 2013

Bennett

policy, and even foreign policy. They are also national symbols in which citizens can take pride

(Shtilmark, 2003), making them (potentially) important for building national identity (Nye, 2006).

Not all citizens though, particularly indigenous peoples, are included in, respect, or even take an

interest in the legitimacy of national parks, making them densely layered spaces of contested and

contingent sovereignty domestically and internationally – a palimpsest of sovereignties. Moreover,

both Russia and Canada draw on international regimes such as the United Nations Convention on

the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Committee to actually defend their national sovereignty in

disputed waterways. Scrutinizing governments‘ motivations behind conservation measures in the

Arctic, where questions of sovereignty and ownership are crucial, is key to understanding whether

genuine efforts are being made to protect the Arctic environment. Through the practice of

stewardship, the state is able to securitize spaces like contested waterways by acting in the spirit of

conservation. Canada and Russia in particular therefore enroll nature and the environment in their

securitization strategies.

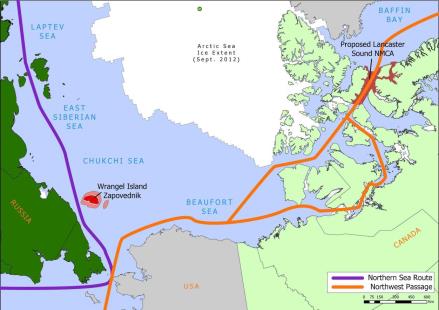

Overview of Wrangel Island

zapovednik

and Study Area for Proposed Lancaster Sound NMCA.

Arctic Environmentalism in Transition

There is a disparity between the regional and global scale of many of today‘s environmental

problems, such as climate change and black carbon, and the national level at which they are tackled

(Kuehls, 1996). Consequently, as with many ecosystems that cross national borders and boundaries,